Baba Wague Diakite is an artist who defies categorization–a fact that reveals as much about the limits of artistic categories as it does about Diakite’s multiple talents. Both Malian and American, the artist has been a resident of Portland, Oregon, for more than fifteen years. He expresses himself in many media, from ceramics and textiles to storytelling and architectural sculpture. He creates both “high art,” made for display in museums and galleries, and “craft,” household objects that are made to be used. His work playfully draws together elements associated with “traditional” Malian and “contemporary” American cultures.

The quotation marks that surround several of the terms used above draw attention to their provisional nature and to Diakite as an artist whose career demonstrates their essential artificiality. His work grows out of the diversity of his experiences, which place him as much between categories as within them. Though he draws on a cultural heritage of which he is proud, Wague does not seek to express an essential Malian-ness or African-ness but instead his own humanity. In his words: “My work is not tied up with traditional concerns or techniques…. As much as I am proud to introduce a little of my culture through my art, I do not consider my work to be particularly African.” In this, Diakite shares the concerns of many contemporary artists from Africa, who seek to transcend the labels by which the art market organizes its categories, too often blocking entry to those whose work is not neatly classifiable.

Diakite was born and raised in Kassoro, a small village in the Fouladougou region that lies west of Bamako, the country’s capital. He credits his grandmother’s stories, which mesmerized children at family gatherings, with instilling in him the creative spirit he brings to every aspect of his work. He moved to Bamako in the late 1970s, joining his parents. Diakite has had no professional training, but from an early age he showed a talent for artistic expression, beginning with the creation and performance of puppet shows. I first met the artist through his paintings made using bogolan pigments, which are associated with a uniquely Malian textile known in the United States as “mudcloth.” He learned the technique, customarily the exclusive domain of women, from his mother during a visit home to Mali in 1987.

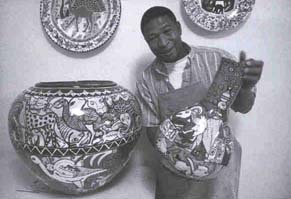

Since his move to the United States in 1984, Diakite has focused much of his artistic effort on ceramics, also considered to be “women’s work” in Mall. He creates vessels, tiles, plates, and figurative sculpture using a variety of techniques; some pieces are wheel thrown, others slip-cast, carved, or handbuilt. He fires his work in an electric kiln and uses brilliantly colored synthetic glazes–both distinctly non-“traditional” techniques. For Diakite, distance from “tradition” permits greater freedom to experiment: “Traditional artists work in one straight line of thought: to do things the way they have been done in the past. Putting too much creativity into it can cause a problem. Being in the United States, I realize that it is great to respect the past, but also having freedom in art is one of the best things you can have.” He recognizes that the women who make ceramics in a “traditional” manner also work creatively, some producing “fabulously sculptural functional ware.” Yet he clearly separates his innovative approach from that of artists whose work is more recognizably “traditional.”

Africanist art historians have devoted much effort, especially in the past decade, to combating stereotypical views of traditional arts as static, unyielding in the face of individual creativity. Two recent issues of this magazine, in fact, featured studies of individual artists, demonstrating the extraordinary creativity that informs their production in “traditional” contexts (“Authorship in African Art,” special issues Winter and Spring 1999). Diakite shares the views of many artists I worked with in Mali: for them, indigenous arts represent a point of departure for innovations that integrate distinctly contemporary influences, and the notion that they should work in a distinctly African (i.e., traditional) style is a source of frustration. Diakite has found that living in the United States frees him from the expectations that too often color the reception of his work among collectors.

Along with ceramic sculpture, Diakite has created large-scale installations for the Oregon Zoo, Oregon State University, and (in collaboration with his wife, sculptor Ronna Neuenschwander) the North Precinct Community Policing Center in Portland. His largest commission, not yet completed, is to be installed at Disney World in Orlando; it consists of a mural eighty-four feet long and five bronze medallions twelve to fifteen feet in diameter, which will be set into a floor. The artist has published two award-winning children’s books based on African folktales and illustrated with his ceramic tiles. His current projects include the establishment of a cultural center outside Bamako, where he hopes to offer American visitors an opportunity to become immersed in Malian culture, facilitating the same understanding across cultures that he himself has experienced after immersion in American culture. By moving beyond the divisions that often segregate both people and art forms, Diakite eloquently demonstrates the interconnectedness that animates the universe.