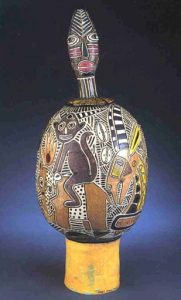

Ce Djan (The Tall One), 2000. Handbuilt vessel with lid, underglazes, crackle glaze; 102cm (40″). The University of Iowa Museum of Art. Iowa City.

Diakite describes this piece as a little granary or storage pot, based on the large pots that stand at the corner of family compounds in Malian villages and, less frequently, in urban neighborhoods. The shape of these storage vessels evokes, for Diakite as for others raised in rural households, the power and mystery of unseen riches, for the food and other goods held in these containers are the focus of much longing among small children. Diakite equates himself with such a vessel, for his own young children view him as the powerful repository of goods and knowledge. This piece is richly adorned with linear patterns and fanciful creatures, including a ci wara figure, the distinctive wooden antelope headdress worn at agricultural celebrations among the Bamana.

Right:

Kote (Spinner), 2000. Handbuilt earthenware, underglazes, glaze; 68cm (27″). Courtesy of Pulliam-Deffenbaugh Gallery, Portland, Oregon. This brilliantly glazed piece is multilayered in its signification. The Bamana word kote refers to a child’s top made of a snail shell. Kote is also a dance characterized by spinning steps. For Diakite, the act of spinning has particular significance, for he views it as a metaphor for human interaction: “Spinning means a person is open; you can see every dimension around a person who is spinning. Just turn around and you will realize that the things around you stay in place, so the person standing still can see you from all sides.” Spinning, he notes, is clearly the natural state of things, for the earth itself is always turning. The adornment of this piece reflects Diakite’s interest in animal characters, which play key roles in the stories and lessons he heard as a child at his grandmother’s house.

Top:

Koro Kara, 2000. Handbuilt earthenware, underglazes, glaze; length 51cm (20″). Courtesy of Pulliam-Deffenbaugh Gallery.

As they are in much of Diakite’s work, animals are key iconographical elements of this piece, their symbolic roles based as much in the artist’s own imagination as in indigenous Malian thought. For him the snail represents courage and morality. The animal’s hard shell conceals its interior, just as a morally correct person will conceal a secret despite pressures to reveal it. Diakite sees the frog that adorns the side of this long-legged snail as another symbol of courage, and of perseverance as well. He explains, “In the snow of Alaska, you can find frogs. In the deserts of Timbuktu, you can find frogs. People underestimate the power of frogs.” This fantastic creature, then, offers a model for ideal behavior.

Bottom:

MishiKun Masks, 2000. Handbuilt earthenware, underglaze, glazes, porcupine quills; right, 61cm (24″); left, 71cm (28″). Courtesy of Pulliam-Deffenbaugh Gallery.

These elaborately painted masks represent a pair of horned animals, each with a porcupine quill sprouting from its head. As with paired ci wara antelope headdresses, one is male (the larger of the two) and the other female. Diakite has used clay rather than wood to portray the masks and marionettes used by young people in Malian villages and small towns. There, groups of masks are danced to entertain audiences at public festivities, such as harvest celebrations. They refer to the importance of the relationship between humans and animals. Animals are sources of food and transportation, and at a metaphorical level, in stories and myths, they serve as models for human behavior.

The Tales I Tell, 1996. Earthenware, acrylics; 102cm (40″). Courtesy of Pulliam-Deffenbaugh Gallery.

Because he travels between two homes, Mali and the United States, Diakite finds himself serving as an interpreter for his family and friends in both places, relating stories about life elsewhere. The fantastic head atop this cylindrical body stands for Diakite himself, his hand on the front of the body, gesturing as he describes faraway places. The interlocking people, animals, cars, and houses that encircle the piece illustrate the interlaced lives and stories that draw distant people closer together.

Djeliba, 1999. Earthenware, underglazes, glaze. Diameter 51cm (20″). Courtesy of Pulliam-Deffenbaugh Gallery.

Along with elaborate vessels and sculpted creatures, Diakite creates platters, plates, bowls, and a variety of other forms that are sold as both functional objects and works of art. This platter celebrates djeliw (sing. djell), the Mande historian-singers who play powerful social roles as repositories of detailed historical knowledge and supporters of important families. At the center of the composition, a singing djeli plays his kora, the harp-like instrument closely associated with djeliw throughout the region. The densely painted border that surrounds the powerful musician-historian represents all of history, evoked by the djeli’s epic songs.